Crossroads

A Transgender Education Platform for Greek Life Students

UX Research | Project Management

Crossroads was a year long initiative and passion project that acted as my masters thesis. The Georgia Tech HCI masters program gave us the flexibility to choose our own problem space, and we defined the scope of this project ourselves. We were responsible for identifying a problem to solve, defining user characteristics and preferences, developing a prototype, and evaluating our solution.

This work is also published in the Journal of LGBT Youth. Click here to read it!

Overview

Problem

Transgender and nonbinary individuals are a particularly vulnerable subgroup of the LGBTQ+ community, especially in college Greek environments. Not only do these environments make it more difficult for students to be themselves and/or come out, but those that do often have to become the primary educator in their Greek communities about transgender/nonbinary issues.

Project Goals

How can we use educational technology to teach cisgender Greek students about transgender and nonbinary individuals in their community?

How can we utilize educational technology to promote transgender and nonbinary inclusion, understanding, and acceptance in college Greek environments?

My Contribution

UX Research: literature review, survey design, interviewing, affinity mapping, focus group design and facilitation, and usability testing session design

Project Management: organized and monitored team schedule, and acted as the primary stakeholder and interviewee contact

Team

Stephanie Baione and Yiming Lyu

Advisors

Jessica Roberts and Audrey Reinert

Timeline

May 2020 - May 2021

Tools

Miro, Figma, BlueJeans, Qualtrics, Adobe Illustrator

Background

Transgender and nonbinary individuals are a particularly vulnerable subgroup of the LGBTQ+ community. Not only is this community small in number, about 1.4 million in the United States (0.6% of the population), they also face increased risk of bullying, violence, and health/medical challenges. These issues are further magnified by college environments, especially ones with outdated school policies relating to dress code, housing, and bathrooms.

Greek Life has a complicated relationship with the LGBTQ+ community. Again, transgender and nonbinary individuals face special difficulties due to their non-heteronormative identities clashing with Greek communities’ cultural foundations of traditional masculinity and femininity. Despite these clashes in identity, many LGBTQ+ students still participate in Greek Life. For transgender and nonbinary Greek students, however, there exists a constant fear that coming out may change their relationship with their Greek friends and the community overall. A Greek transwoman, for example, may ask herself: “Will my fraternity still accept me as a member if I come out?”

There is also a general lack of LGBTQ+ education within Greek communities - LGBTQ+ trainings on our college campus are only optional for Greek chapters, and many do not see the need to engage in LGBTQ+ trainings unless they know their chapter contains LGBTQ+ members.

For the transgender and nonbinary individuals that do come out to their Greek organizations, they often bear the burden of educating their entire community about transgender and nonbinary issues. This role can be intense and stressful for many reasons ranging from the students still trying to make sense of their own identities to them simply not wanting to play the role of constant educators.

In the hopes of addressing this gap in education on transgender/nonbinary issues and allyship in Greek communities, our team underwent a year long study to examine our university’s Greek environments, its transgender members, and the potentially effective ways to implement an educational technology that would mitigate this educational burden on the Greek transgender and nonbinary population.

Yiming and me at the Atlanta Pride parade in 2019.

Defining Some Terms…

I’ve provided the definitions for some common terminology I will be using throughout this piece below. If you are unfamiliar with LGBTQ+ terminology and are interested in learning more, here is a great visual for defining the expanded LGBTQ+ acronym, and here is an article on terminology for LGBTQ+ allies.

Cisgender:

a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex

Transgender:

a person whose sense of personal identity and gender does not correspond with their birth sex

Non-binary:

a person whose sense of personal identity and gender don't fall into the category of male or female

Project Goal

How can we use educational technology to teach cisgender Greek students about transgender and nonbinary individuals in their community?

How can we utilize educational technology to promote transgender and nonbinary inclusion, understanding, and acceptance in college Greek environments?

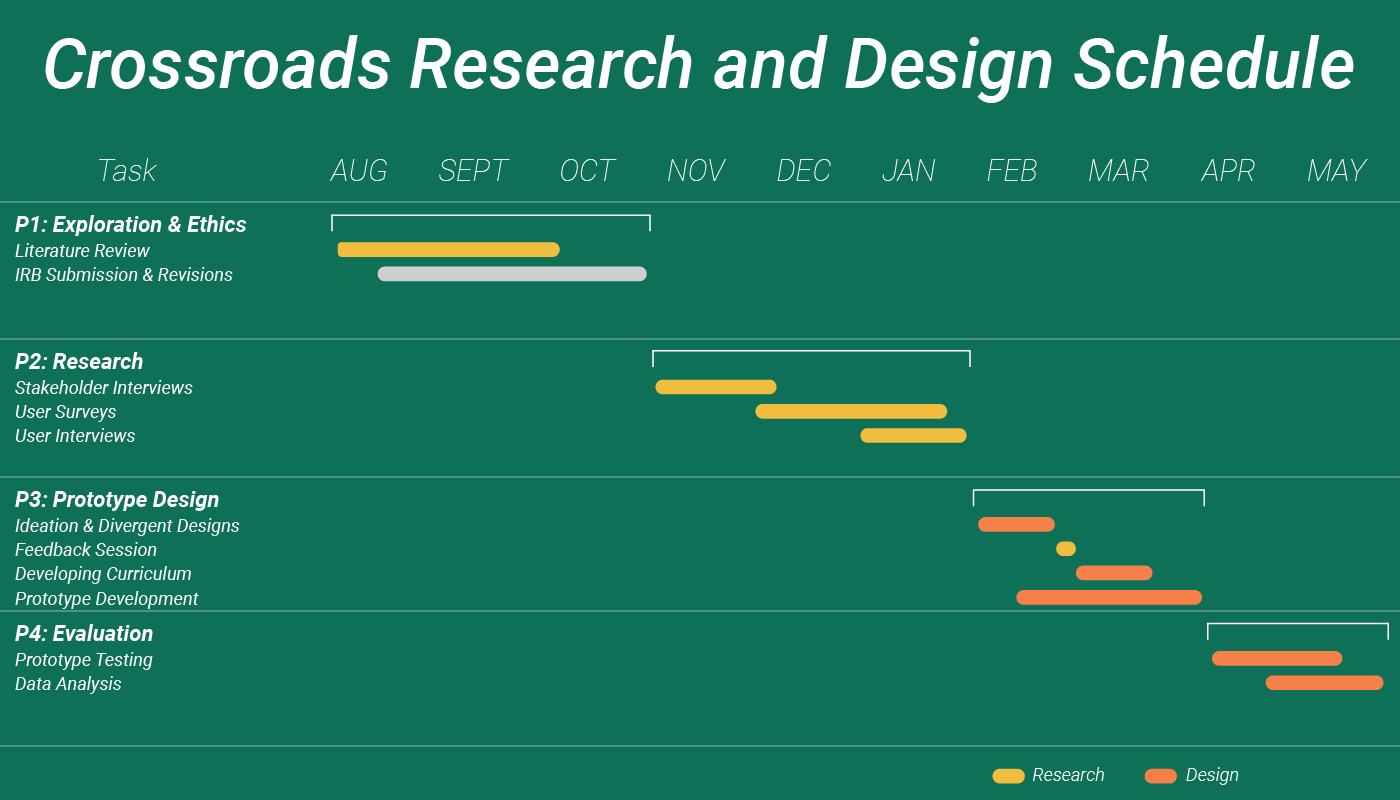

Project Timeline

This project took place from May 2020 to May 2021. As the team’s project manager, I was in charge of developing our team’s schedule, communicating with our advisors, and ensuring we stayed on track.

This schedule provides a summarized view of all the research and design work Yiming and I conducted throughout this project. I acted as the project lead for all research initiatives, and Yiming led design initiatives.

This project’s main stages, simplified.

Dark green denotes research work, and light green denotes design work.

Grey represents work that was neither research nor design.

Phase 1: Exploration and Ethics

Studying Existing Work and Receiving IRB Approval

Literature Review

Our Literature Review was the foundation of our entire project. Because neither Yiming nor I are transgender/nonbinary nor members of Greek communities, we relied significantly on previous research to assist us in our problem definition. This work consisted of analyzing existing research from many topics including but not limited to: promoting LGBTQ+ wellness, transgender/nonbinary individuals’ unique needs, college safe spaces, Greek Life and gender, cisgender college students’ perceptions of LGBTQ+ communities, LGBTQ+ educational technologies, Greek allyship, and education to benefit minority communities.

Research Goals: This research was integral for providing us with the scaffolding necessary to support our work when pitching it to stakeholders, advisors, and the IRB alike. Through this work, we hoped to demonstrate that our project fulfilled a tangible need that is currently unaddressed both at Georgia Tech and in the wider research community.

My Contribution: Yiming and I split the literature review evenly, and we read and analyzed approximately 30 academic sources alongside numerous non-academic articles, blogs, and news pieces.

Findings: Through this research, we developed a breadth of knowledge about our problem space and identified what gaps in existing work we may be able to fill by pursuing this project. These findings would prove valuable throughout each stage of the project moving forward, ranging from pitching the project to the IRB, getting backing from stakeholders, and in justifying our design decisions.

If you are interested in reading the detailed results of the literature review, see the Introduction and the Background and Related Work sections of our research paper here.

IRB Approval Process

The IRB was one of our greatest challenges early on in this project: we spent just over 2 months working towards IRB approval and went through 7 revisions in total. While these delays put strain on our work timeline, it was incredibly valuable for us as researchers to be forced to think through the minutia of our proposed methodology. Neither Yiming nor I had ever written in-depth consent forms or put much weight to details like where we stored our interview notes. But you quickly learn that, when you are working with vulnerable populations, details are integral to your participants’ safety. For example, should a closeted transgender Greek student volunteer to interview with us, they could hypothetically incur risk if the signup process was not confidential, if the interview location was in Greek spaces, if anyone overheard our conversation, if any personal details/interview notes got leaked, etc. This is all to say that, while the IRB revisions were frustrating at times, it was important to remember that the IRB was not about us, our thesis timeline, or our masters’ degree — it was about our participants. And we have a responsibility as researchers to ensure that our methodology actively protects them so our results can serve them.

Phase 2: Research

Aligning with Stakeholders and Talking to Users

Research Methods

1. Stakeholder Interviews

2. User Survey

3. User Interviews

Findings: Through affinity diagramming, we identified four broad areas that influence Greek education, LGBTQ+ trainings, and transgender needs/experiences: individual, educational, social, and institutional factors. The following is one example of each:

Institutional: the existing structures and restrictions in Greek Life

Social: frats are traditionally masculine, but gender neutral frats break the mold

Educational: mandatory trainings often frustrate participants

Individual: many LGBTQ+ students are not ready to come out

Our stakeholders also offered a number of proposed solutions to these factors that we would consider when developing solutions. They ranged from the critical social design implication of not ‘outing’ transgender participants to the institutional design implication of making transgender issues into Georgia Tech’s issue through our solution.

1. Stakeholder Interviews

For needs gathering, we employed the use of participatory design: we regularly consulted experts within the Greek and LGBTQ+ communities in order to better frame our understanding of our problem space. We reached out to GT faculty, Greek Life leaders/administrators, and LGBTQIA+ Resource Center staff. Each interview was conducted via BlueJeans and lasted about 60 minutes.

Research Goals: Our goal throughout all the stakeholder interviews was to learn about existing efforts surrounding transgender and nonbinary inclusion on campus as well as receive advice on how to best focus our research and design scope. We had a number of specific goals for each stakeholder type:

Faculty: Understand how their expertise (i.e. Gender Studies) relates to our subject matter and what their experience has been working with and teaching transgender and nonbinary students.

Greek leaders/administrators: Learn how Greek councils and chapters’ attitudes differ on LGBT+ issues as well as about what educational training and programs already exist on campus.

LGBTQIA+ Resource Center staff: Identifying major problems that LGBTQ+ individuals face in Greek Life and important considerations to make when interacting with transgender and nonbinary participants.

My Contribution: I maintained relationships with the stakeholders via email, facilitated the user interviews, and took notes throughout.

2. User Survey

Our user survey was a mechanism of accessing the broader Greek community in a way that would have been impossible with user interviews alone. It examined general sentiment from Greek students with regards to their reasons for joining Greek Life, their experience with diversity in the community, and their experiences with transgender individuals. We were also attempting to reach transgender individuals and asked them if they were out in their community and why/why not. The survey was distributed using a Greek Life listserve. It was sent to about 4,000 people, and we received 222 responses.

Research Goals: Our user survey had two major goals. First, we hoped to better understand student motivations for joining Greek Life and the general sentiment towards diversity and transgender/nonbinary inclusion. Secondly, we intended to use the demographics results of the survey to better define our user characteristics. As a final note, we also utilized the survey as a mechanism for finding willing cisgender and transgender interviewees for the user interview phase discussed below.

My Contribution: I designed the survey in Qualtrics and worked with school administrators to have the survey distributed.

Findings: After analyzing our 222 survey responses, we found that 199 of them reported affiliation with the Interfraternity Council (IFC) and the Collegiate Panhellenic Council (CPC) Greek chapters. Therefore, due to the abundance of information we gathered on these groups, we decided to focus our efforts on designing a solution for those subsets of the Greek community. Additionally, after examining respondents’ motivations for participating in Greek Life, we found that our users are motivated by an interest in self-betterment, and cultivating diverse friend groups. These sentimetns are coupled with an overwhelming emphasis on maintaining a strong sense of community in Greek communities. These characteristics would later define our intended user group and impact design decisions.

Findings: In addition to learning the intricacies of being a Greek student at Georgia Tech, we gained a critical insight: our user group has an extremely wide range of LGBTQ+ knowledge. Regardless of their LGBTQ+ knowledge, however, all our cisgender participants were interested in learning more about transgender populations and how they can support them (this is rather intuitive since they expressed interest in the interview/our topic space, but the existence of interested students is important nonetheless). These learnings helped us recognize that an effective educational tool for our users needs to be designed such that new users can learn something regardless of their LGBTQ+ knowledge, and the technology needs to be woven into both the community structure and community motivations for learning.

3. User Interviews

User interviews were a critical opportunity for us to acquire rich and detailed information from cisgender and transgender users. We recruited for our interviews using participants who left their emails for further research in our survey as well as from our personal circles. We interviewed 18 people in total, 4 of which were transgender. These sessions were semi-structured, conducted remotely via BlueJeans, and lasted 45-60 minutes each.

Research Goals: The purpose of our user interviews was to better understand both cisgender and transgender students’ perceptions, experiences, and perspectives about our topic space. Our goals for these interviews varied: for transgender students, we were primarily interested in learning about their Greek experience from recruitment to active Greek membership to graduation. For cisgender students, we were both interested in the general dynamics and structure of the university’s Greek Life as well as these participants’ general transgender knowledge and experiences (if any) with gender non-conforming individuals in their Greek communities.

My Contribution: I designed the interview guide, reached out to participants, and facilitated the interviews.

Research Findings

This is an intro. Will change later.

User Characteristics.

Our primary users are cisgender members of Georgia Tech’s IFC and CPC Greek communities. These individuals were motivated to join Greek life due to a strong desire to join a community. Additionally, they generally report being interested in self-betterment, cultivating diverse friend groups, and learning about LGBTQ+ and transgender populations. These users exhibited a wide range of knowledge about LGBTQ+ issues, ranging from being highly informed and involved to self-reporting as unknowledgeable.

Based on these characteristics, we developed the hypothesis that an effective educational tool for these users would need to be designed such that it can be easily woven into both the community structure and community motivations for learning, as well as be adaptable for different levels of initial LGBTQ+ knowledge.

4 Critical Insights.

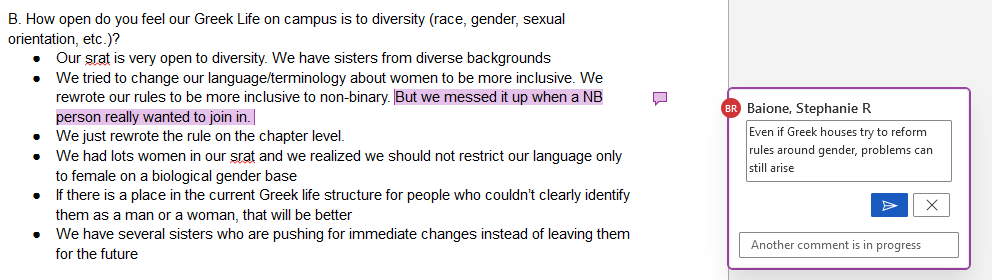

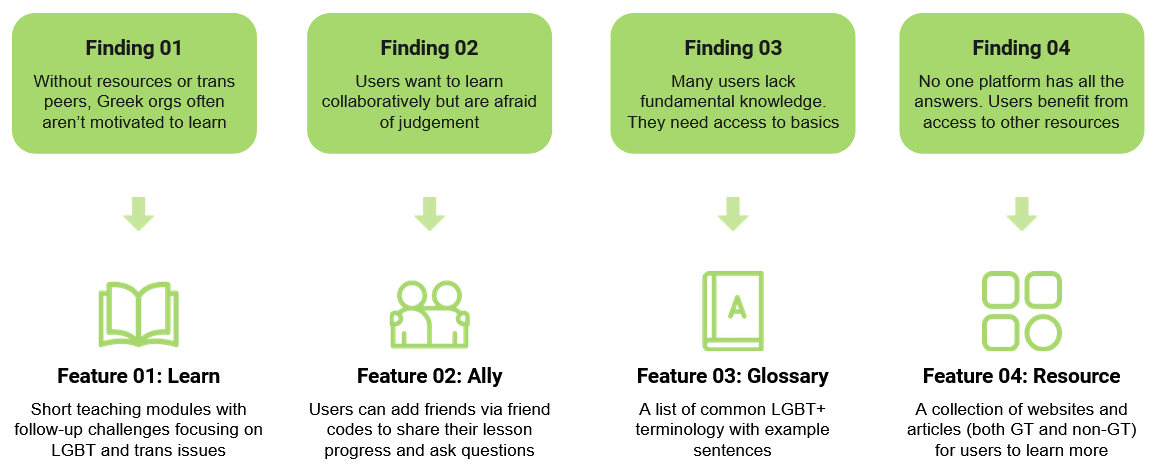

In an attempt to distill all our learnings from the research stage, we organized our results into 4 major categories. The findings are shown below as well as some extra details about how those findings were developed. These findings will be turned into design features in Phase 3: Design.

Our user interviews taught us that Greek orgs usually need transgender/nonbinary members advocating for education in their community to generate interest. It is worth mentioning that cisgender members can also act as promoters for this education.

Through our stakeholder interviews, we learned about creating effective teaching environments. Many stakeholders asserted that, even if students want to learn, they may feel uncomfortable admitting to a lack of knowledge on certain subjects, especially LGBTQ+ topics.

Our survey and user interviews helped us to recognize that, not only is there no required LGBTQ+ trainings in Greek life, but there is also a wide range of LGBTQ+ knowledge and awareness.

In our literature review, we were unable to find any centralized, holistic LGBTQ+ education. The only universal educational tactic was the presence of additional/ external resources for seeking out more information.

Phase 3: Design

Divergent/Convergent Design and Participatory Design via Stakeholder Focus Group

Brainstorming

A screenshot of our brainstorming ideas organized in Miro.

Using the information from our research phase as a guide, we engaged in a divergent brainstorming session. We wrote down as many ideas for solutions that we could think of in a 30 minute time period. Then, we examined our possible solutions as a team and either created new ideas or built on existing ones. Through this process, we generated 50 rough ideas that we narrowed and refined during a design ideation session, shown on the right.

In order to better sort through our initial brainstorming ideas, we organized them into three tiers. A tier referred to ideas that definitely had potential, B tier was for ideas that had probably had been done before or were good but infeasible, and C tier was for ideas that were impossible, definitely infeasible, or simply bad. By organizing our ideas in this manner, we were able to isolate ideas we thought were worthy of our attention and expand on them. In the image on the right, blue sticky notes represented an idea we thought was worthy of further ideation.

Next, we reorganized our 15 best ideas into categories based on the central issue the solution idea hopes to solve. We did this with the intention of generating only one final idea per category - we wanted to diversify the final solutions and avoid selecting multiple ideas that solve the same problem.

A screenshot of our best brainstorming ideas organized by category.

A closeup of our ideas from the Social Platforms category.

Once we had organized our 15 ideas, we realized that we would need to better define each idea in order to make a decision for how to narrow them down further. For each idea, we asked ourselves a number of questions (the light yellow stickies in the image on the right), including:

What is the idea?

What are we teaching?

How will we teach it?

Is there any existing work?

Why should this work?

What are the expected pros and cons?

How does this relate to GT Greek Life?

We quickly realized that, if we were unable to answer most of the above questions for an idea, it was likely not feasible. This removed three ideas from the pool (the greyed out titles on the right).

Next, we asked ourselves how long we thought each idea would take to implement (represented by the red, yellow and green sticky notes to the far left of each idea). We had less than 4 months to design, prototype, and test our idea, so we needed to be conservative with the amount of work we took on.

Finally, we met as a team and rated each idea on a scale of 1-5 before selecting the most highly ranked ideas from the Individual Training, Social Platforms, and Simulations categories. This concluded our brainstorming phase, and we set out to expand upon the 3 selected divergent design ideas, to be explained in the next section.

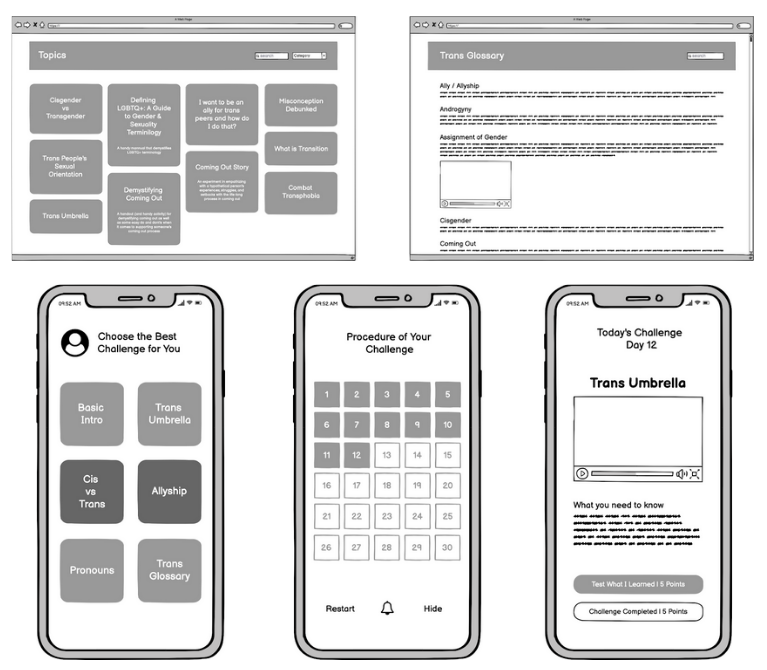

Divergent Design

The following are the three divergent designs Yiming and I developed based on our brainstorming. We worked to ensure that each design was unique and addressed our problem space using different platforms, educational styles, and types of interactions.

Upon finalizing these ideas, we realized that we needed to realign with our stakeholders, as we needed their insights to assist us in selecting a final convergent design. This feedback will be discussed in the next section.

1. Self-Guided Training App

An app with a collection of modular lessons based on Safe Zone Training Scheme that utilizes GT examples and scenarios

Education Style: Formal teaching emphasizing basic knowledge

Platforms: website and/or mobile application

Features:

modular lessons pulled from Safe Zone

Daily challenges/reminders to practice lesson learnings

Glossary of LGBTQ+ terminology

Collection of articles on LGBTQ+ issues

2. Ally Mentorship App

An app that connects cisgender people who want to be better allies and LGBTQ+ Greek students who are interested in mentor-mentee relationships with reference to learning about inclusivity

Education Style: Informal teaching encouraging discussion between users

Platforms: mobile application

Features:

A sorting quiz to evaluate new members’ knowledge of LGBTQ+ issues

A matching system to pair mentors with mentees

Public and private chats

Daily/weekly educational objectives to guide mentor/mentee conversations

3. A ‘Coming Out’ Simulator

A pre-written conversation that has a number of branching paths depending on the player's knowledge of trans people. Player can choose dialogue options that advance their personal learning.

Education Style: Highly informal teaching emphasizing empathy

Platforms: video game or interactive narrative

Features:

A branching narrative story with choice-based decision-making for the user

Allows the user experience coming out as a transgender individual

Stakeholder Feedback

In my humble opinion, this initiative was the highlight of all our research for this project. It is also the best example of how we utilized participatory design (PD) to facilitate decision-making. Maybe it was the rush of succeeding to get 8 busy stakeholders in one BlueJeans call and guiding them to generate meaningful and intriguing discussion, but I felt more like a UX research professional conducting this one hour session than I have felt in all my research experience thus far. Suffice to say, I’m very excited to tell you about it.

Below are some screenshots of the feedback session in Miro. The image immediately below is a high-level view of the entire session. I will also show some zoomed-in pictures of individual frames further down.

Feedback Session Structure

We started with a 3 minute introduction (1) and warmup to using sticky notes in Miro (2) followed by a 3 minute refresher on the state of our research (3). At this stage we also defined what we wanted from our stakeholders: to identify which teaching styles would be most effective for GT Greek Life and which design features are most important to our educational tool.

From here, we introduced our three divergent ideas one at a time (4-6). We dedicated 13 minutes per design idea. I gave a verbal explanation of the idea and prompted the stakeholders to write down the strengths, challenges, and opportunities associated with each idea. The remaining time was spent allowing the stakeholders to discuss sticky notes they considered especially important.

After examining each divergent design, we dedicated 3 minutes to ranking the divergent designs (7) on three criteria: feasibility, creativity, and the quality of the learning experience. And finally, we ended the session with 10 minutes to identify what features were most valuable (8) for the success of an idea. This was also an opportunity for stakeholders to recommend any other features that would be integrated well into a design idea.

Closeup: Strengths, Challenges, and Opportunities for the Self-Guided Training App

Closeup: Rating the Divergent Designs

Closeup: Most Valuable Features

Feedback Session Results

Overall, the feedback session generated two outcomes. First, using our ranking system we identified our stakeholder’s choice for the most effective divergent design idea: the self-guided modular training app. Second, using the most valuable design features we identified which characteristics of the other two design ideas were most valuable for an effective LGBTQ+ educational tool. These learnings allowed us to converge our design process on an improved version of the proposed self-guided modular training app that utilized valuable features from the other ideas.

We cannot stress enough the value that this initiative had for our project. By utilizing PD, we received quality feedback from experts in an environment that encouraged a form of peer review. As new ideas and feedback were shared on the Miro board, stakeholders agreed, disagreed, or built upon ideas together. This process also refined the quality of the stakeholder feedback. If feedback was highlighted by multiple stakeholders, we knew incorporating that feedback would address a wider range of issues in our problem space. In the next session, we will discuss how these findings transmuted our original ideation for the self-guided training app into superior hybrid of select ideas.

Convergent Design

To generate our convergent design, we considered our Self-Guided Modular Training Application and how we could develop a feature that satisfied our research insights. The 4 features we generated were called Learn, Ally, Glossary, and Resource.

Using these features as a guide, we then created some low fidelity prototypes of each. However, we quickly realized that a prototype of this scope would be impossible to fully implement in our remaining time (about 3.5 months). Therefore, we made the decision to focus on the Learn feature for the remainder of the project.

We identified the Learn feature, shown on the far left, as the most important component of our design to implement for a proof of concept evaluation. This feature was selected over the others because this project’s main goal was to create an educational tool - while Ally, Glosssary, and Resource contributed to the educational experience, the Learn content was at the center of the application’s functionality and purpose.

“But wait… we have the content, but what’s the curriculum?”

This was a funny moment for Yiming and me. In retrospect it feels obvious that copying over Safe Zone and It’s Pronounced Metrosexual content verbatim into our prototype would be insufficient for our purposes, but this was also the first time in our HCI careers that we had to practice content design. It unsurprisingly came with its own set of design challenges. As I sat with a blank excel spreadsheet on one monitor and the Safe Zone curriculum on the other, I started asking myself a number of questions, such as:

What foundational knowledge is necessary for teaching transgender/nonbinary content?

How do we balance the time spent on foundational LGBTQ+ content versus specific transgender/nonbinary content?

Where do you even start when introducing the idea of transgender identity?

How do we keep lessons short but still provide a depth of information?

What topics/information matters the most?

After considering these questions, identifying learning objectives, and consulting with our advisors, we generated the final curriculum for our prototype, shown below:

The first module (left) focuses on foundational LGBTQ+ content. Pulled primarily from Safe Zone, this content focuses on framing the user’s idea of allyship and introducing foundational LGBTQ+ terminology. The second module (right) dives deep into transgender/nonbinary identity. It introduces the idea of biological sex and gender being two independent entities, explains critical terminology, and gives users important tips on how to make transgender/nonbinary peers feel safe and seen.

I could go on and on about the surprising nuance that went into this curriculum development process, but one thing I can say with confidence after completing our evaluation is that this curriculum needs a lot of work. Put simply, this is a challenging topic space to teach: our society uses the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ interchangeably, and it can take time to unlearn these terms’ synonymy. Combine this mental block with resistant political discourse and the design decision to not directly involve transgender/nonbinary individuals in the educational process, and our curriculum runs the risk of being discredited and/or dismissed. The current curriculum undoubtedly shows success and potential as a proof of concept, there are many things I’d like to iterate on in future work.

High Fidelity Prototype

While I was creating our curriculum, Yiming was working on our app’s visual design. I was not significantly involved in this process, so this is an opportunity for me to talk about what an amazing designer Yiming is! I was so grateful to have him working with me on this project - he breathed life into our prototype in a way that I can only hope to emulate some day.

Here are some examples of our high fidelity prototype, including: a view of the teaching modules (far left), lesson lists within a module (left), a vocabulary screen (right), and a lesson complete screen (far right).

Activity Types

As Yiming was implementing my curriculum, he created a number of ‘activity types’ that were used throughout the prototype. These aimed to streamline learning by presenting new information in repeatable visual schemas.

Vocabulary Cards

Emphasizes basics and allow users to revisit unfamiliar terms

Edugraphics

Simplifies complex information and allows users to learn through engagement

Action Guidelines

Frames guidelines as achievable and adds interaction to lists

Daily Challenges

The activity types above focused on in-lesson learning. Our final activity type, the daily challenge, was designed to be presented to the user at least 24 hours after completing a lesson. The daily challenges pull from the idea of using spaced repetition models to solidify learning over long periods of time, and intended to facilitate self-reflection, learning assessment, and knowledge extension.

Prototype Demo

Once we had completed both the curriculum and the visual design, we combined the two and assembled a functional 9 lesson prototype. You can demo the lessons below. If you are unable to view or click through the experience, you can also do so here.

Phase 4: Evaluation

Prototype Testing and Findings Analysis

Prototype Testing

Our evaluation of the final prototype was conducted with a convenience sample of four cisgender participants from our personal connections at Georgia Tech. Three of these participants were alumni of Greek organizations and one was an active Greek student. Additionally, we recruited one transgender Georgia Tech graduate who had participated in the earlier survey and interview phases.

This evaluation consisted of a 10 day remote, asynchronous evaluation. We hoped to gauge the perceived value of each lesson as well as user enjoyment. For the cisgender participants, we were interested in the quality of the learning experience, while for the transgender participants, we wanted to validate that the educational curriculum effectively represented transgender individuals. The steps that went into our evaluation are articulated below:

Stage 1: To prepare participants for this evaluation, we briefed them on the evaluation stages and how to use Figma. We also we had them complete an assessment of their LGBTQ+ knowledge so we could evaluate learning at the end of the evaluation.

Stage 2: This was the core of the evaluation where users interacted with our prototype’s teaching modules at a set cadence. Each day, the participants received a text message from the researchers (to simulate app notifications) that provided them with links to the activities they needed to complete. Daily interaction with the prototype lasted no longer than 15-20 minutes. After completing their daily activities, the participant reflected on their experience with the prototype by completing a 3 minute evaluation survey on Qualtrics.

Stage 3: After 10 days, the participant completed a 45-minute interview to discuss their experience with the prototype and filled out the post-evaluation assessment, which was identical to the pre-evaluation assessment.

Note: in this evaluation, we were not evaluating the quality of the prototype’s educational content in comparison to any other educational LGBT+ tools; rather, we were aiming to prove that the prototype’s educational content can stand on its own as an educational platform.

Analysis: Quantitative Findings

The core of our analysis of individual lessons came from the quantitative findings collected during the post-lesson feedback survey. Participants were asked to rate their perceived value and enjoyment of each lesson using a Likert scale.

Module 2: The Trans Umbrella

Module 1: The Basics

Keeping in mind that we had a small sample size for this study, we can tentatively say that our proof of concept prototype was successful with respect to creating a valuable and enjoyable learning experience. For future work, we plan to take the lessons that were voted particularly high or low, identify what led to those scores, and use the best elements of those lessons to improve the others.

Analysis: Qualitative Findings

The core of our evaluation learnings came the post-evaluation interviews. While analyzing our interview notes, we identified common and/or interesting themes, discussed below:

Striking visuals make learning more fun

Lesson 1.4, which had the most dynamic visuals of all our lessons, was highlighted as being enjoyable and fun. This finding is reflected in our quantitative findings as well. Conversely, lessons that were more heavily dependent on text received average or lower reviews.

Quizzes are the preferred daily challenge format

Participants liked the direct feedback afforded by quizzes. Unlike self-reflection challenges, quizzes provided a method of immediately evaluating their learning and identifying topics they don’t understand.

Providing resources encourages further learning

Feedback to including external resources was mixed. Some participants felt requiring external resources in lessons made the lessons too long, but others felt that being linked to external resources motivated them to do more in their communities.

Modules need more examples and immersion/hands-on practice

Our transgender participant felt like some elements of our transgender module were lacking in terms of how deeply we covered certain topics. Cisgender participants felt like a lot of information was thrown at them all at once. Further iterations of this work would need to consider which topics should be broken up into their own lessons as well as alternative methods of communicating the information.

Teaching empathy goes both ways

One cisgender participant felt antagonized and talked down to by our lessons. This feedback makes a strong case for considering the framing and tone used when explaining new concepts, especially ones with political associations. Extending empathy to our learner will help them develop empathy for others in turn.

Users enjoy ‘quick tips’ in addition to lessons

While there was mixed reception to the ‘action guidelines’ activity type, cisgender and transgender participants alike thought there was value in providing checklists with advice for how to behave like a transgender ally.

Final Evaluation

1. Summary

2. Research Limitations

3. Self Reflection

Summary

The above topics spaces were identified as Crossroads’ major contributions to the space of educational technology.

Over the course of a year, Yiming and I set out to develop an educational technology capable of integrating with the Georgia Tech Greek community and teaching the cisgender members about transgender and nonbinary individuals. Our final prototype, designed by utilizing participatory design with stakeholders and users alike, came to be after various stages of divergent and convergent design and iteration. The proof of concept prototype for Crossroads, a self-guided modular training application, showed promise as a new learning environment characterized by short lessons and spaced reinforcement. There is much left to implement and test in the Crossroads platform, as well as revisions to be made based on evaluation feedback, but this research suggests the Crossroads platform stands firm as an onramp to LGBTQ+ terms/conversations while also providing new context for Greek environments and new reinforcement methods for LGBTQ+ learning overall.

Research Limitations

This study was an exploratory proof of concept utilizing an initial prototyping phase to prove feasibility of the Crossroads tool. This exploratory work, while exhaustive in examining user needs and stakeholder perspectives, was confined to Georgia Tech’s Greek environment, and this limited user scope prevents us from making overarching claims about transgender education in Greek environments as a whole. Additionally, this work did not extend to all of Georgia Tech’s Greek Life: the majority of our Greek Life research focused on the subset (222 of 4000) of Greek students who engaged with our survey, and it can be assumed that our work was biased towards individuals who already display a willingness to engage in LGBTQ+ discussions.

Also due to the exploratory nature of this work, we were not trying to directly empirically evaluate our prototype compared to other equivalent teaching platforms. One of our evaluation’s goals was to provide learners with an accessible and easy-to-use onramp to LGBTQ+ terms and conversations when compared to existing educational platforms. However, since all the evaluation activities were done in an online environment with many technical restrictions, we could not compare the effectiveness of our design with other equivalent platforms in this study. Instead, we were only able to see if our prototype itself was effective in LGBTQ+ education.

Finally, the Crossroads platform we tested was incomplete both in terms of its content and implementation. For the purposes of this work, we utilized an interactive high-fidelity proof of concept prototype made in Figma, which has many restrictions in user interaction. As a result, a number of our initial design ideas could only be either partially developed, or developed in an alternative way that was feasible in Figma. Additionally, our initial evaluation of the platform revealed that, should Crossroads be fully implemented, it would benefit from fully implementing other features than just the ‘Learn’ category.

Self Reflection

I have been searching for a way to employ my professional expertise to help LGBTQ+ communities since I was an undergrad; this project was truly a dream come true in that regard. It was also by far the largest and most abstract research activity I’ve undertaken to date. For a long time, even after we had settled on a topic space, I was worried that this project space would end up being a dud; that all the passion and work we were putting into our research would yield no results. Perhaps I need to take advice from my past self, who wrote a reflection about my Verizon Connect internship and learning to trust your research process. It appears my problem is deeper than that: I need to trust myself and believe in the competency of a research process I design.

That’s not to say I wouldn’t do anything differently if I could start this project over. Our initial research activities, such as the literature review and stakeholder interviews, were perhaps too broad in their exploration. Yiming would often tell me I needed to stop - that I didn’t have to read every piece of published literature to work on this project. Perhaps it was the dead time brought on by IRB delays (and oh would I love to impart my knowledge of that process onto my past self) that left me feeling antsy for something to do, something to learn. Our survey was also too general. We focused too heavily on recruitment environments rather than the holistic Greek Life experience, and didn’t do enough exploration into sentiment surrounding LGBTQ+ and transgender education. Looking back, I’d say the sheer scope of our project combined with the high standards we set for ourselves (this being our master’s thesis and all) had us biting off more than we could chew at times. But perhaps that is also the nature of exploratory work like this - there really aren’t any existing transgender educational platforms like Crossroads, so it’s not like we had the benefit of past work to lean on.

Designing research methods aside, I learned a number of soft skills from this project. For one, I know a lot more about designing educational environments and the work that goes into making platforms both enjoyable and informative. But I’ve also developed a new perspective specifically for designing for sensitive communities. Regardless of our intentions in conducting this research, it can often be a risk for transgender and nonbinary students to openly talk about their identity, especially when it could have an impact on their social lives. We had to ensure that we were taking every precaution such that they were safe to engage in research activities with us without fear of being outed. And perhaps the biggest lesson I learned was that, no matter how much I learn from my research, I always need to seek advise from a variety of transgender and nonbinary advisors before making research decisions. It would be irresponsible of me to try to walk in the shoes of my transgender peers, so it is my responsibility as a researcher to make sure I am walking alongside them instead.

Another thing I’ve learned is that I certainly hold myself to an unachievable standard. Would you believe me if I said I worked on the project of my dreams for a full year, created and validated a proof of concept, submitted a paper for publishing on the topic, but still felt dissatisfied with the results? Well here I am. I find myself wishing there was more time to do everything we couldn’t - to implement all the advice we received in the evaluation and implement the features we had to bench for future work. I want to see this platform through to implementation at Georgia Tech in some capacity. After doing some soul searching, I think this feeling is coming from how, at my core, I wanted to make a positive impact in the lives of Georgia Tech transgender and nonbinary students, and a 2 person team working on a year long exploratory research initiative is woefully inadequate for making something tangible to pass off for development in that time. From this project and the first few months I’ve been working full time at Verizon Connect as a UX Researcher, I’m starting to wonder if researchers sometimes feel trapped in the concepting phase; like they’ll devote everything to a project and immerse themselves in the space only to have to hand it off and move on. Regardless as to whether or not I ever actually get to ‘finish’ Crossroads, I’ll always be holding it and the people it aims to help close to my heart.

This portfolio piece is dedicated to a lot of people.

Yiming: you are an amazing designer and I am so glad we got to share this project. I hope this piece is able to accurately portray how in awe of your work I am and how grateful I am to have had the chance to work with you again.

An incredible thank you goes out to my advisors, Jessica Roberts and Audrey Reinert, as well as my HCI professors. Your support enabled Yiming and me to put our best foot forward when working on this project and create something we are proud to call our master’s thesis.

Also thank you to Georgia Tech Greek Life, Georgia Tech LGBTQ+ communities, and all our participants and stakeholders in this project. This project is truly a product of your advice.

I couldn’t possibly end this piece without also thanking my LGBTQ+ friends and peers - y’all are the reason I developed an interest in this topic space to begin with, and I hope I made y’all proud.

And finally thank you, reader, for coming along on this journey with me.

Check out some of my other work below.